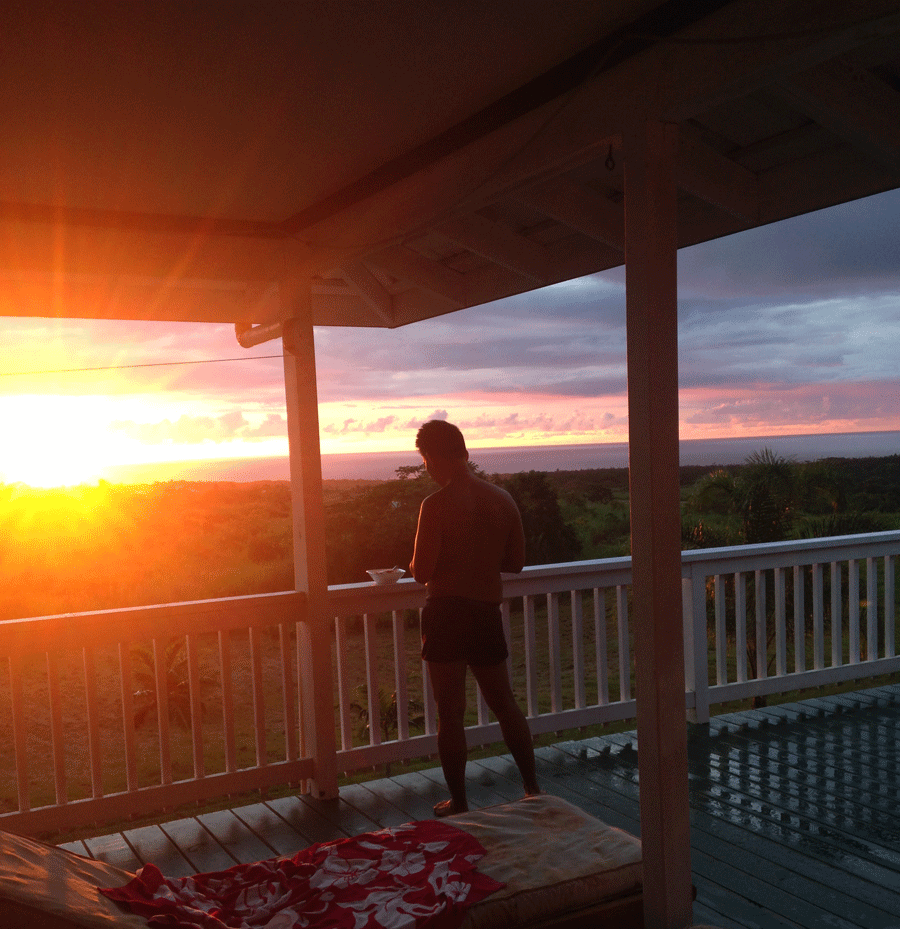

Our first night’s sleep was in a breezeless room. The air was humid, stagnant. Not a drop of rain fell upon the yard. It was too hot for even the grunting pigs to come out.

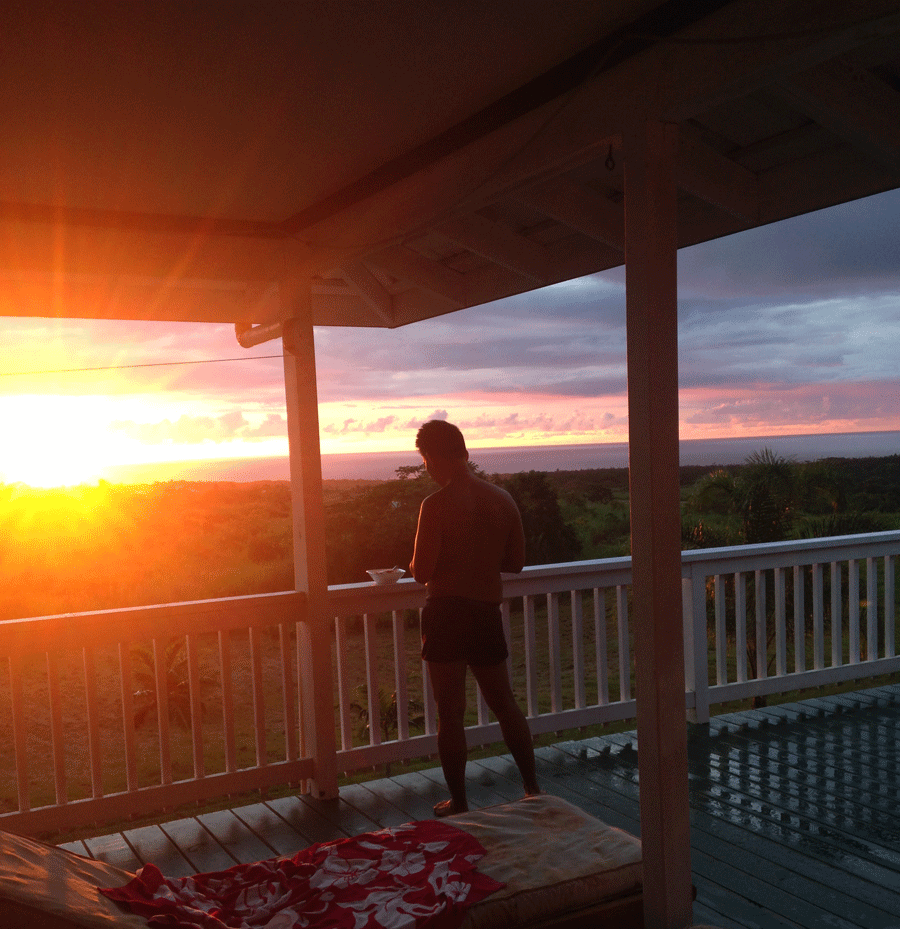

We were, however, granted a stunning sunrise, which pierced the bedroom around six. The day had begun and it was dry and hot. It was stunningly blue, and here and there a cumulus cloud held itself aloft in the vast open sky through magic and fabulousness.

Lower Puna Sunrise, Oct 2014

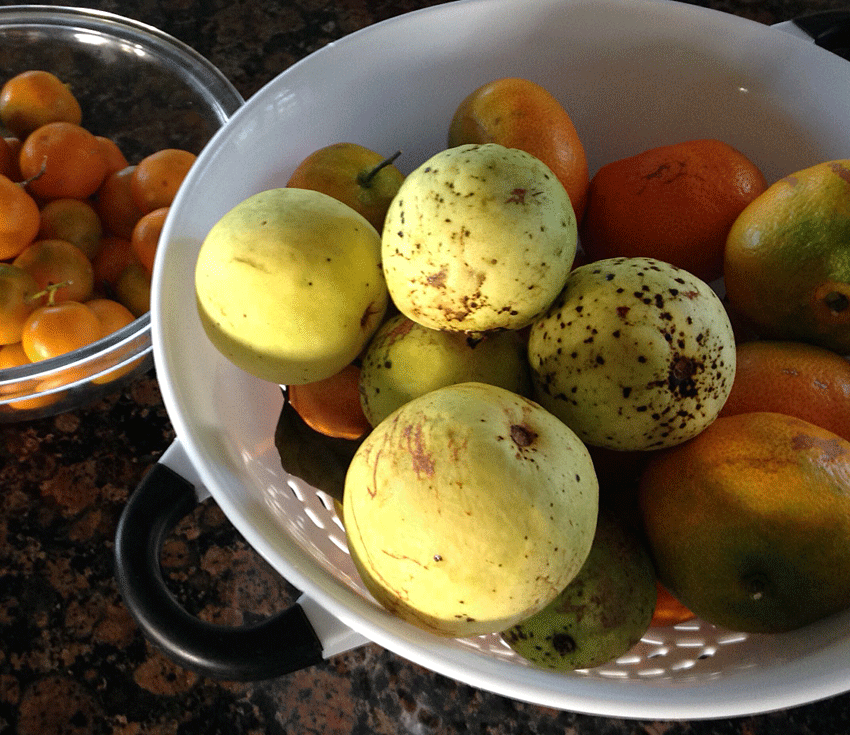

Day One at the house is all about getting situated for the few weeks ahead, making sure you have clothes and toiletries pulled from storage and that your critical needs are on hand: food stuffs for at least a couple lunches and dinners, along with other mandatories such as coffee, yogurt, papaya, vodka, wine…

Aside from grocery shopping, on Day One I don’t like to do anything except acclimate to being back: no extensive yard work or chores; no To Do list creation (the must-do’s will easily sprout over and over like weeds, so there’s no harm in waiting a day to start filling up a list). A little preparatory cleanup around the yard is fine. The goal of Day One is preparation and reimmersion.

There was no coffee in the house. No milk. No nothing except the spices and oils on the cupboard. We’d skipped our grocery trip the night before purely out of fatigue and the desire to be at home and motionless. So we decided to head into Pahoa to buy our bits and eke out a sense of the mood in town.

Tea bed Oct 2014

As I stood on the grassy lawn looking at the weeds twining their way up into the brakes on the car, I noticed what was missing that morning was the scent of grass and greenery being blown in by the trade winds. The air was utterly still. It felt like the planet had stopped hurling through space at 67,000 miles per hour and had come to a standstill.

Of course I knew that wasn’t true. I knew we were still in flight because when I was very young I asked my mother what would happen if the earth stopped spinning on it axis and she said we’d all die. (I presumed the same of making orbit around the sun.) Then I asked her when the world would end and she replied, “When everyone believes in Jesus.”

The carport tent, post-Iselle

At the back end of what used to be the carport is a hill. Five clusters of 20-foot tall bamboo stand like sentries on the hillside, providing some blockage against the full force of the trade winds. Down below the hill is the field, which was unkempt and growing wild with wickedly tall cane grass. In one corner of the field is our test tea bed; it too looked as if it had been consumed by the jungle.

After six months of being away from the house, all I wanted was one day of nothing, a day of reclamation: breakfast, farmers market, grocery, then to rest my lazy bones in the hammock for a while…

I yanked the vines and weed grasses away from the underneath of the car. I was annoyed with the condition of the tea bed and frustrated by the state of the field. I gave a disgruntled look to the yard and then at the cause of it all: our expensive lawn mower, which sat nearby under a brown tarp, out of commission.

Fallen albizias, Iselle Sep 2014

Puna gives in many different ways, not all of them joyous: this time it was the car.

As I backed Arvin’s Honda out the remnants of the carport, the front brakes shuttered. Spasmed. It felt like the whole front end was going to snap off. AAA doesn’t do house calls in these parts, so I figured I’d try to drive off the brake noise and hopefully be able to chock it up to lethargy and under-use.

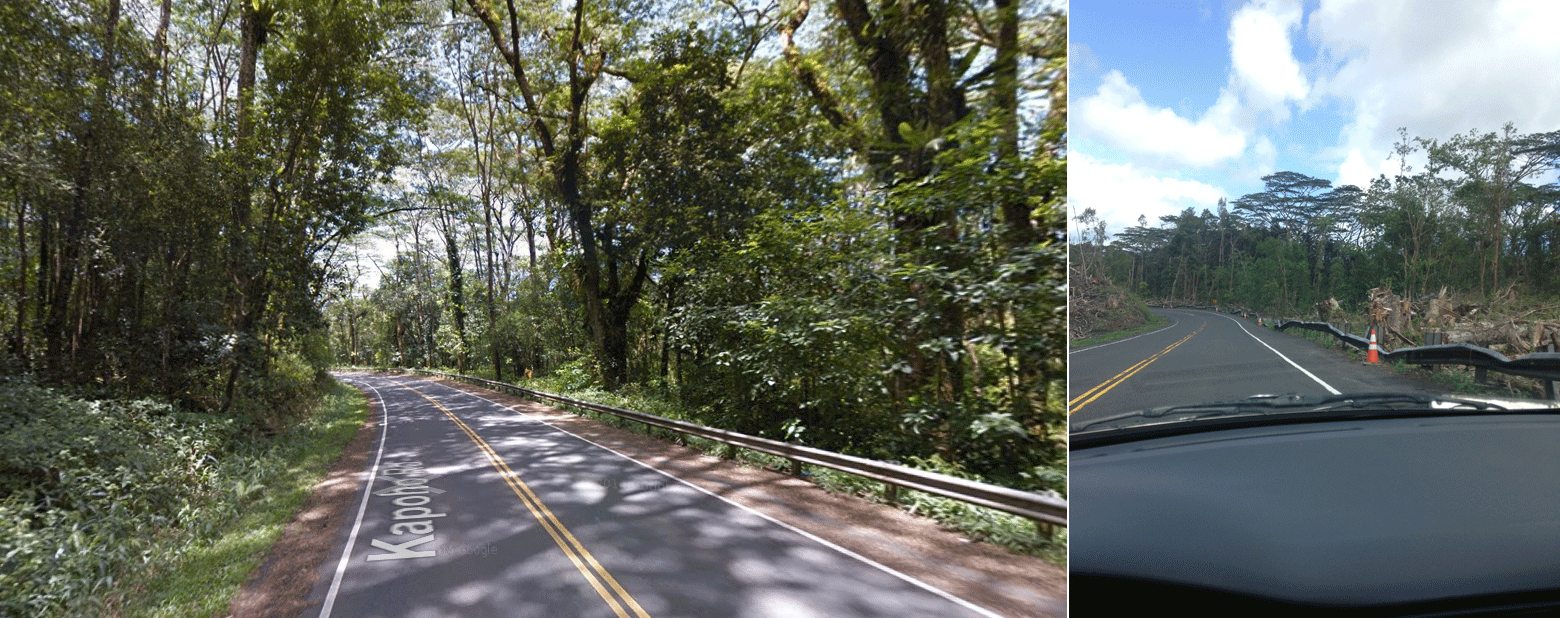

The shuttering did stop once we got moving down the driveway and along the denuded Pahoa-Kapoho Road. When we came to rest across the street from Luquin’s, the Mexican restaurant, the brakes were performing normally. Arvin got out and inspected the tires as a precaution. The front ones were clearly low on air and all four exhibited signs of cracking around the wheel.

Coffee, chilaquiles and a set of Bridgestones

Luqin’s restaurant is in Pahoa village – let’s call it “old” Pahoa. There we had coffee and breakfast, and had the place nearly to ourselves.

The tire shop, which also does vehicle inspections and other maintenance, is in “new” Pahoa, along with the grocery store, drugstore/pharmacy, hardware store, fish market, the new fire and police stations and (regrettably) a Burger King.

After breakfast we drove the half mile or so from old Pahoa into new Pahoa and got a new set of tires. At some point in the (near? very near?) future, this convenience will turn into a 75 mile trek.

Rubicon times

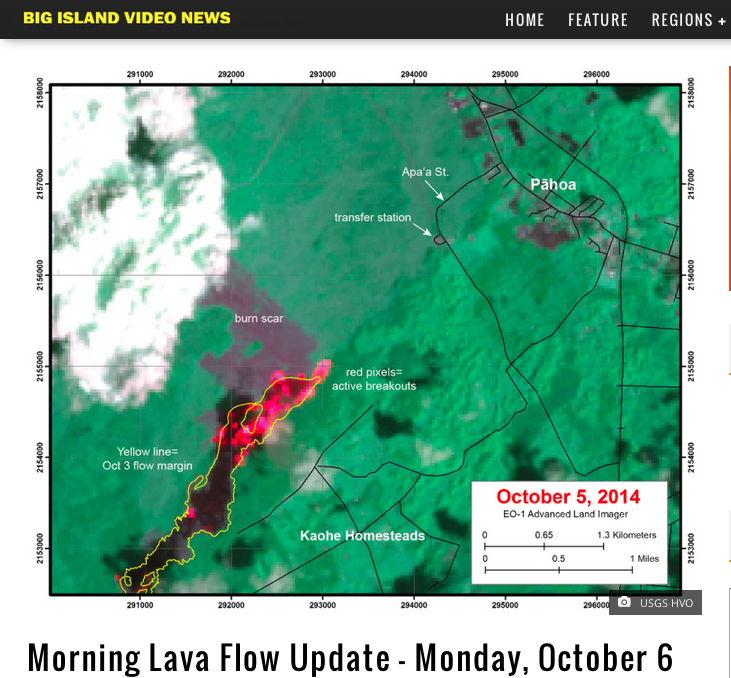

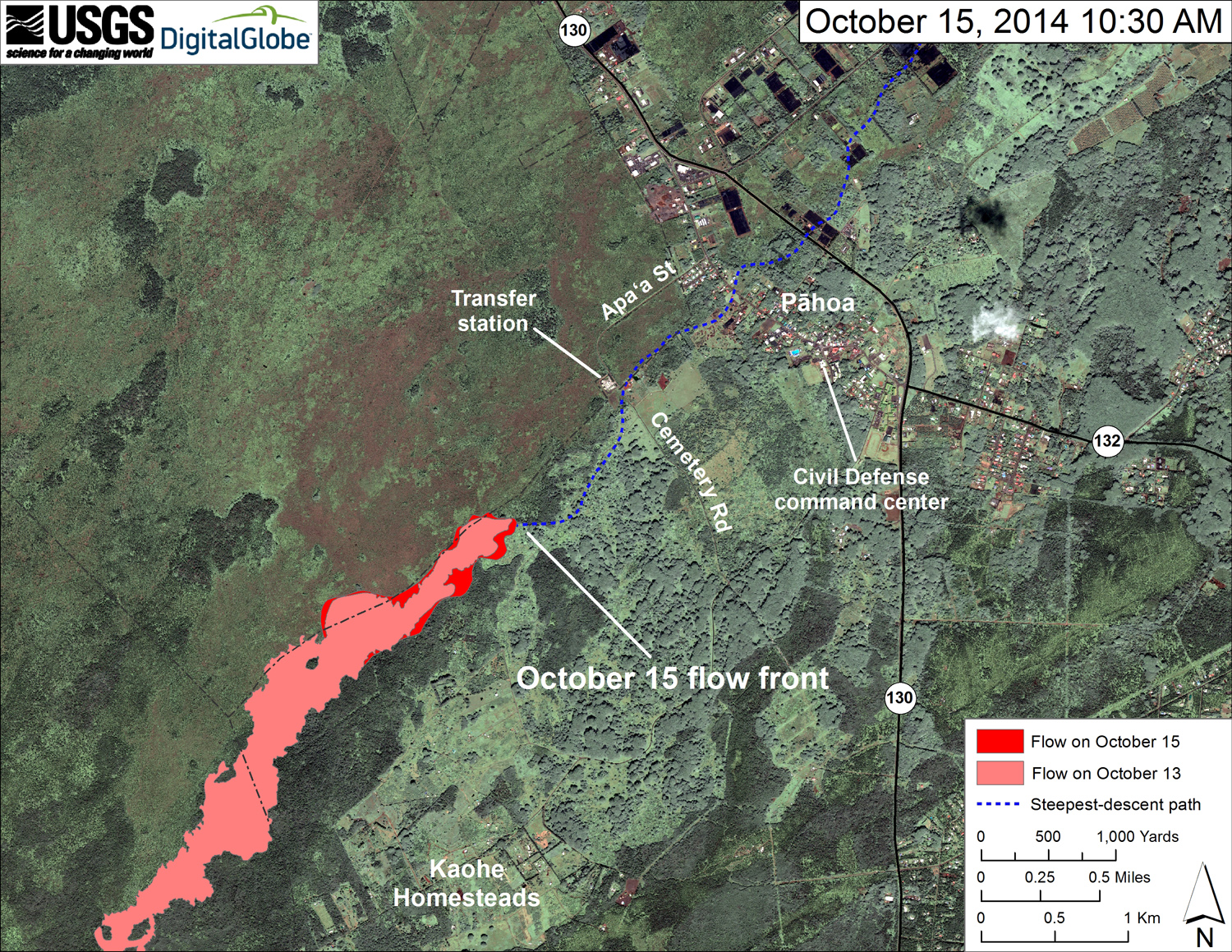

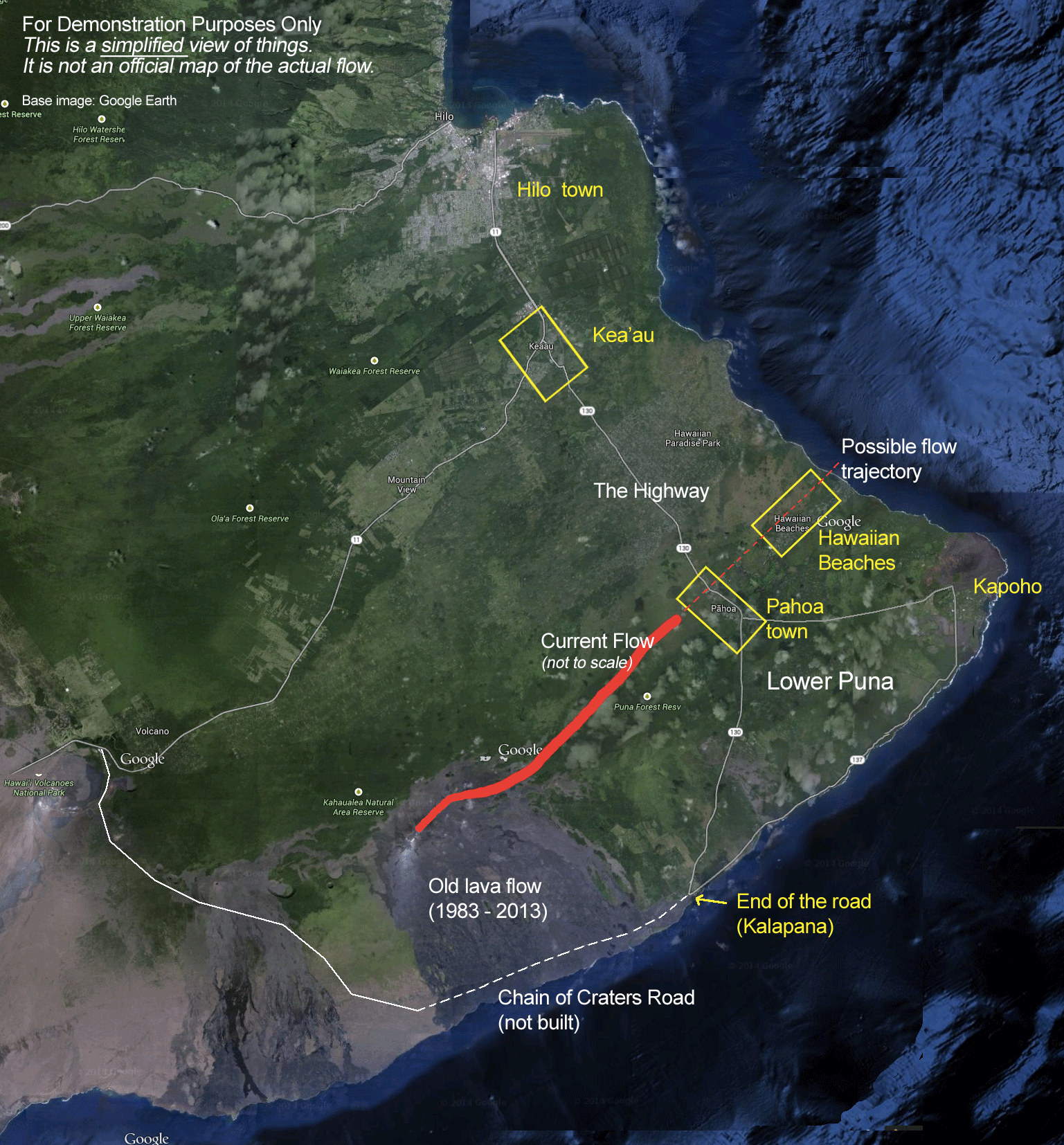

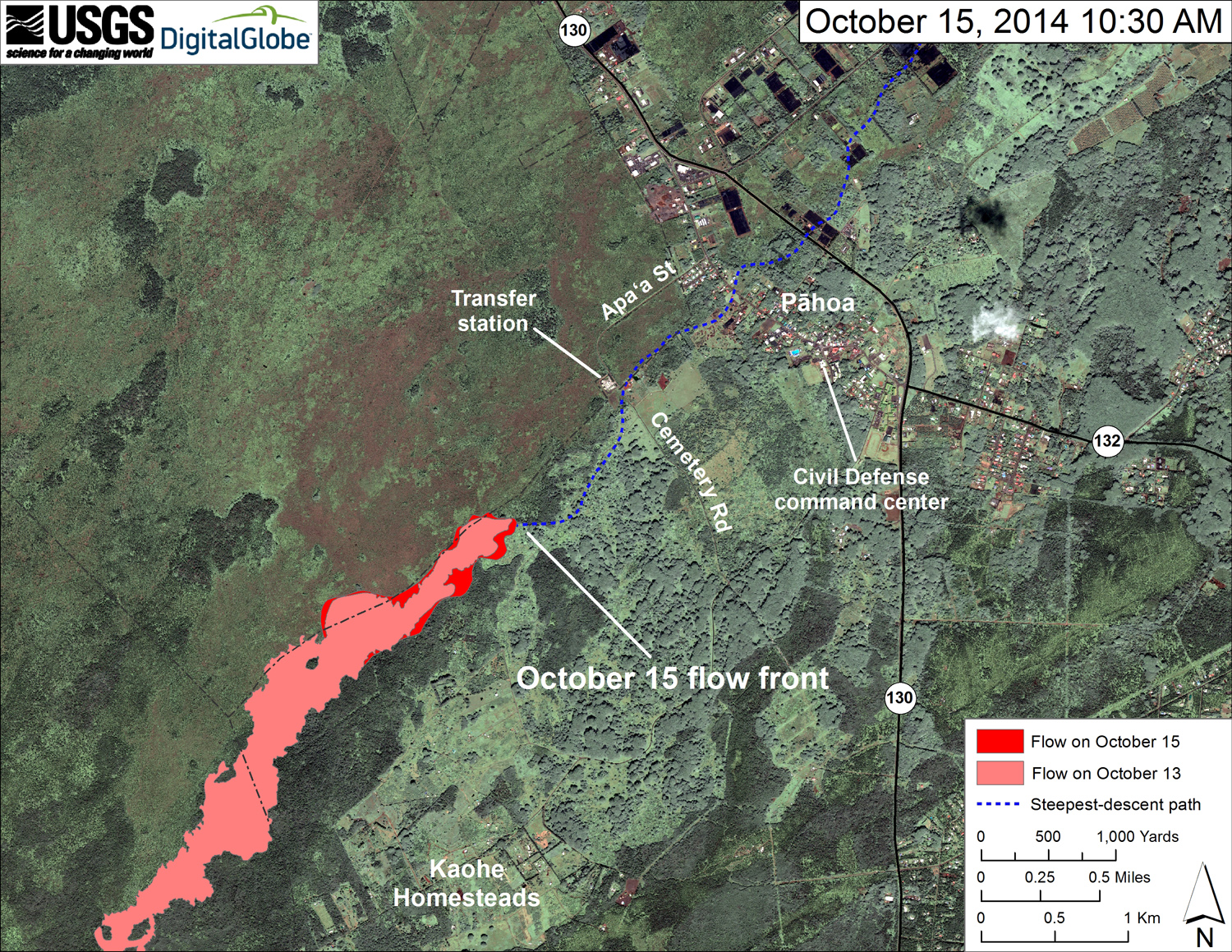

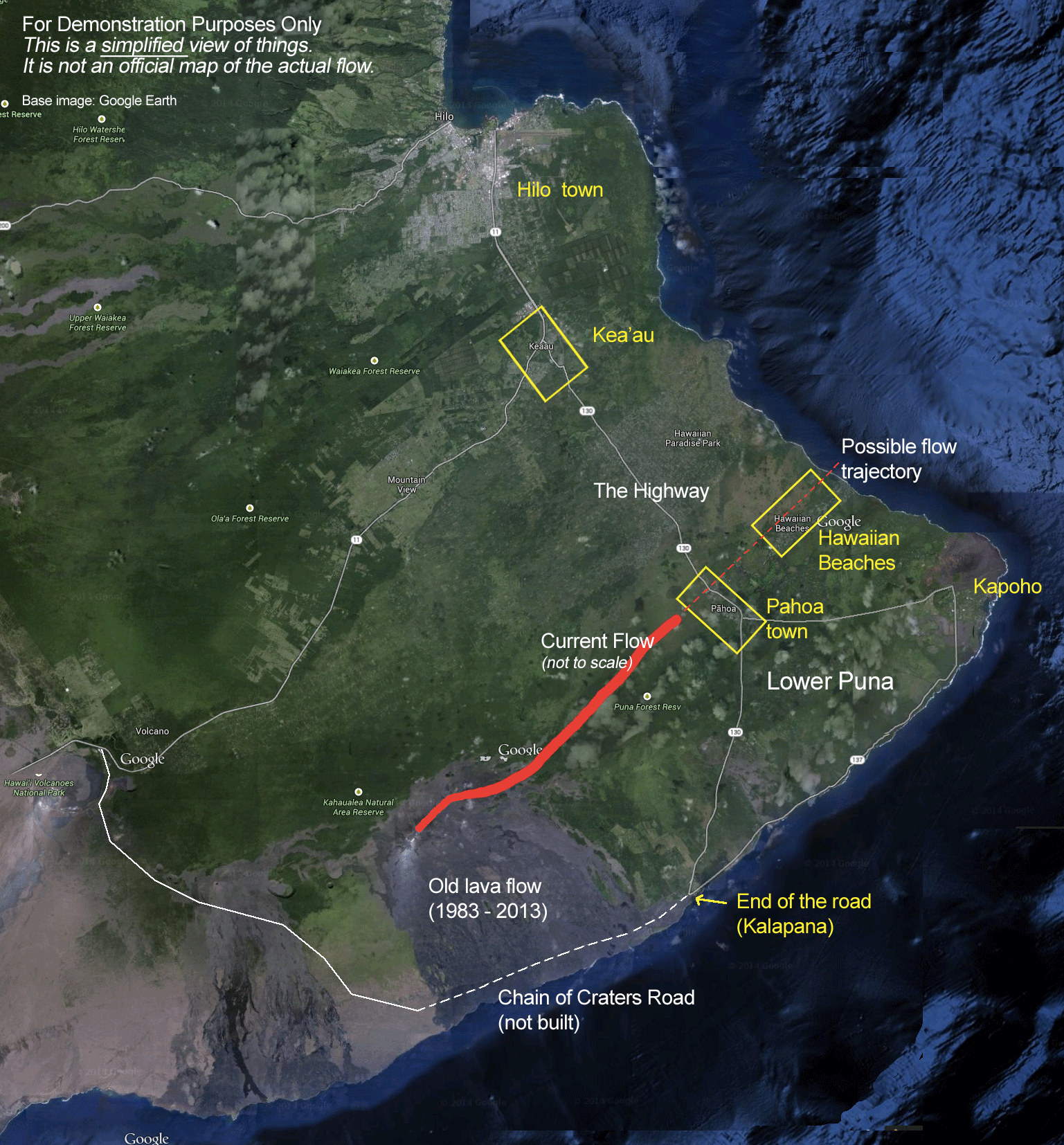

What separates old and new Pahoa is what the geologists call a path of steepest descent (the blue lines on the image below).

Click image to expand…

2014-10-15 USGS HVO map – Pahoa lava flow

Pahoehoe lava flows are slow moving ribbons of lava whose motion is governed to a large extent by fluid dynamics. Their direction and their speed are influenced by topography.

In due time, the slow-moving lava will roll down these lines of steepest descent, filling in the low lying land while building up ridges around which the lava can spread as it continues inching forward, always widening. They tend to start as narrow fingers and progress into wider flows.

Back in early September, when the Pahoa flow was moving quickly out of a crack structure towards a neighborhood above town called Kaohe Homesteads, people flocked into Pahoa for what they figured would be their last supper at the town’s few restaurants. At the time no one had any idea when the flow would hit. The consensus among residents was that the lava was heading for town like a wide-bodied train.

With the lava due to hit Village Road at the end of September and then the Highway perhaps a week later, the realm of the familiar was running out. Lava was our Rubicon, and everyone on this side of the flow would have to choose in relatively short order whether to cross it into a strange new world or stay behind in what was bound to be an even stranger one.

In those first fews, the rumor mill had begun: who was staying, who was leaving, when would supplies stop coming…Everyone become a lava flow expert. A couple of businesses shuttered and left; the majority proudly if cautiously asserted, “We’re staying.”

The initial projections are that the current path of steepest descent which the lava is following will take it past or on top of our transfer station (a beautiful, recently completed $5m structure where we take our trash and recyclables), then through the sparsely populated region between old and new Pahoa.

Residents along the blue line are clearly going to lose their homes. One house along the Village Road has been over-optimistically put on the market for sale; another family across the street from that has parked a shipping container out front to fill and be ready to evacuate.

From this ‘middle town’, the flow is expected to continue onward across the highway and all the way down to the ocean. In order to do that, it will have to pass through the Hawaiian Beaches neighborhood, home to over 4,000 people.

Pahoa lava flow 2014-10-19

Beyond the loss of homes and communities along the path of the lava, what makes the Pahoa flow unique is that the flow is poised to completely cut off Lower Puna’s other 5,000 residents from the rest of the island.

There is one road in and out of Puna right now: Highway 130. As you can see from my sketch above and the USGS map further up, the lava is heading towards the Highway. It was projected to hit early October, but with the changes in speed and volume that timeframe keeps changing.

In the meantime, the County is preparing alternate routes in and out of Puna. A couple miles makai (toward the ocean) runs Railroad Ave, an unused, unfinished old road that the County has recently graded and cindered. When the Highway gets taken out, gravel-topped Railroad will be our primary means of ingress and exgress.

Closer to the ocean lies the old Government Beach Road, a one-lane dirt road with turnouts. This rough stretch of road will be used for evacuation when or if Railroad Avenue gets taken out. (Based on projections and history of the Pu’u O’o lava flow, the more likely word is “when”.)

No way out…?

At every gathering we’ve been to during the past couple weeks, the dominant topic of conversation is the lava flow (unless it’s hurricanes approaching). The panicked sense of imminent doom has been supplanted by fatigue of waiting for the slow-motion devastation to play out. At dinner the other night, a friend remarked, “Just get here, for crying out loud. Take something.”

As much as nobody wants it to happen, we do live on an active volcano. For 31 years, the lava has been flowing primarily to the south – a manageable state of affairs. Now that the flow has shifted north, we’re entering a new state of normal.

Meanwhile, we wait.

Luquins, Pahoa HI